Exhibition

Creative Machine

15 November 2024 - 28 February 2025

Taikang Art Museum, Beijing

29. NOVEMBER 2025 - 1. MARCH 2026

WANLIN MUSEUM, WUHAN

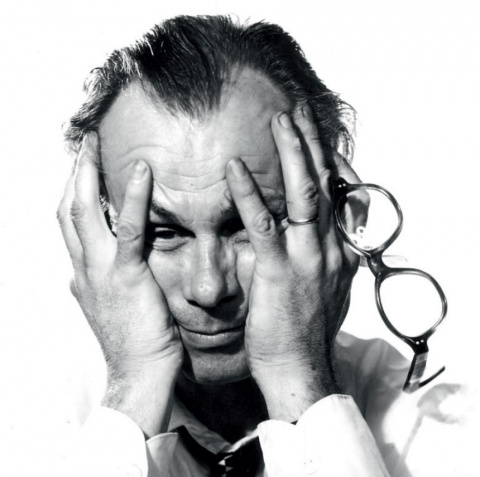

The Avantgardist

Heinrich Heidersberger

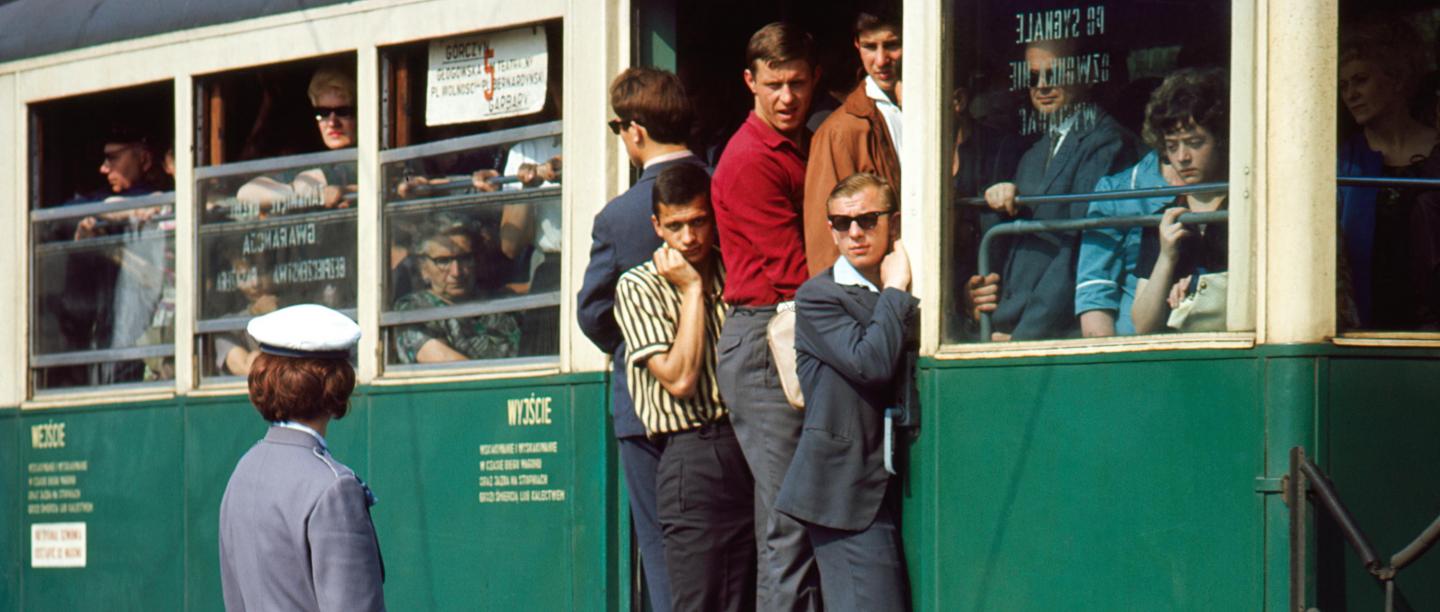

In the words of art historian Barbara Steiner, photographer Heinrich Heidersberger is a “‘modernist’ par excellence” because “like the artistic avant-garde” he sought “to reconcile economy and culture, industry and humanistic ideals, technology and democracy with the help of new technical and economic achievements.” This wonderfully sums up what makes his photographic oeuvre unique and special at the same time: the coexistence of applied and fine art photography.

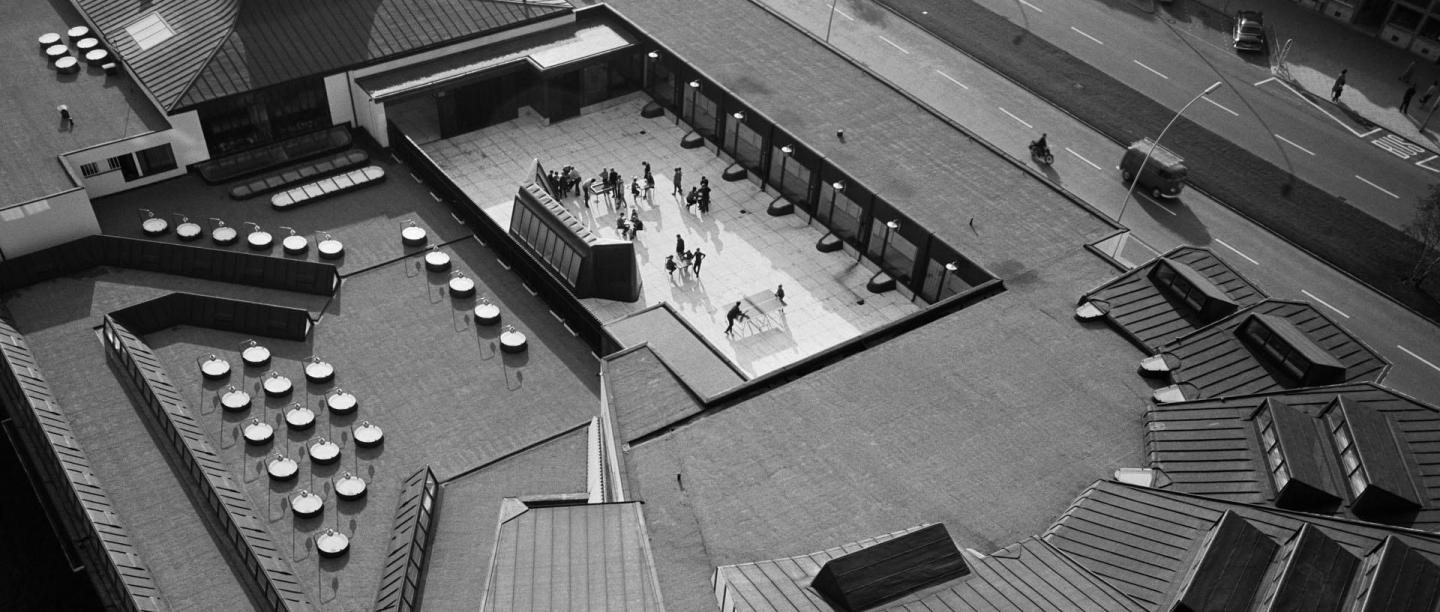

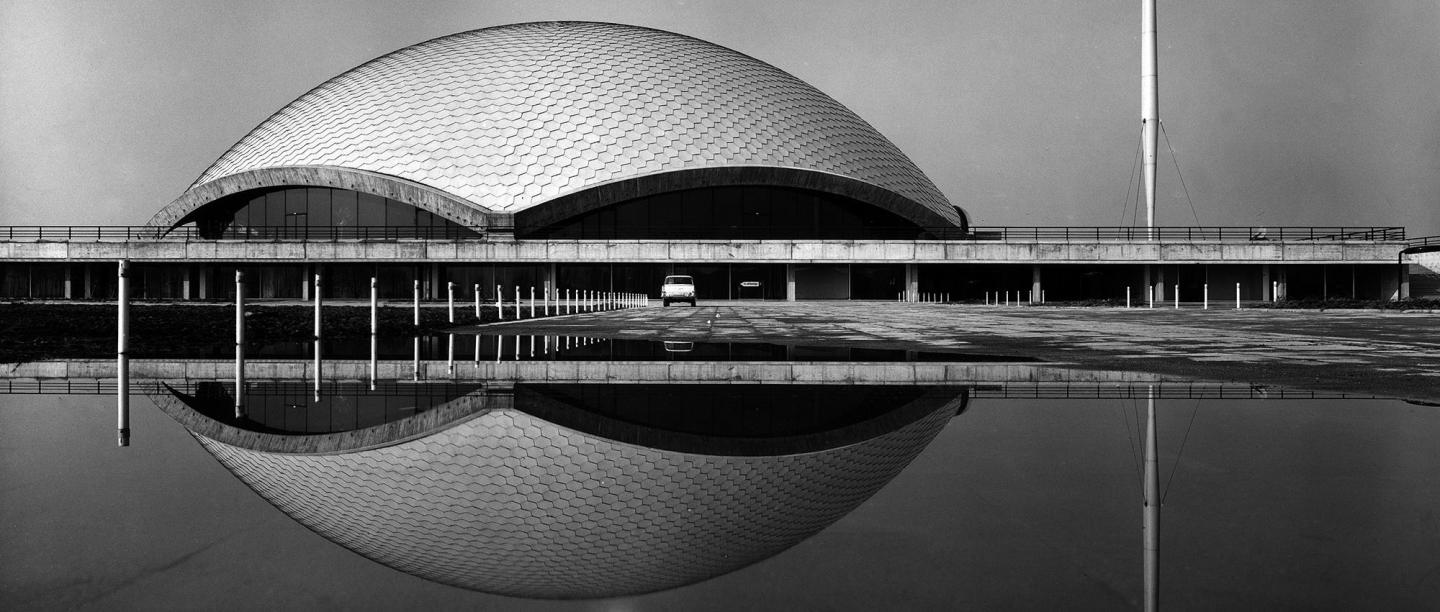

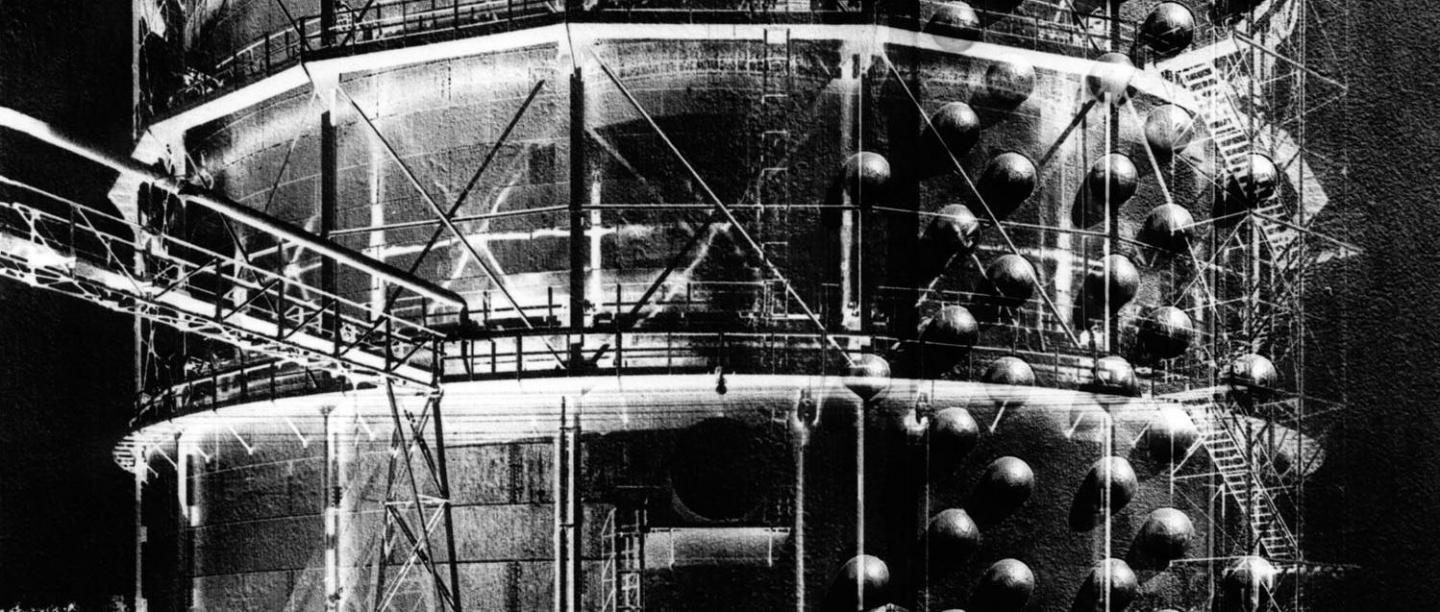

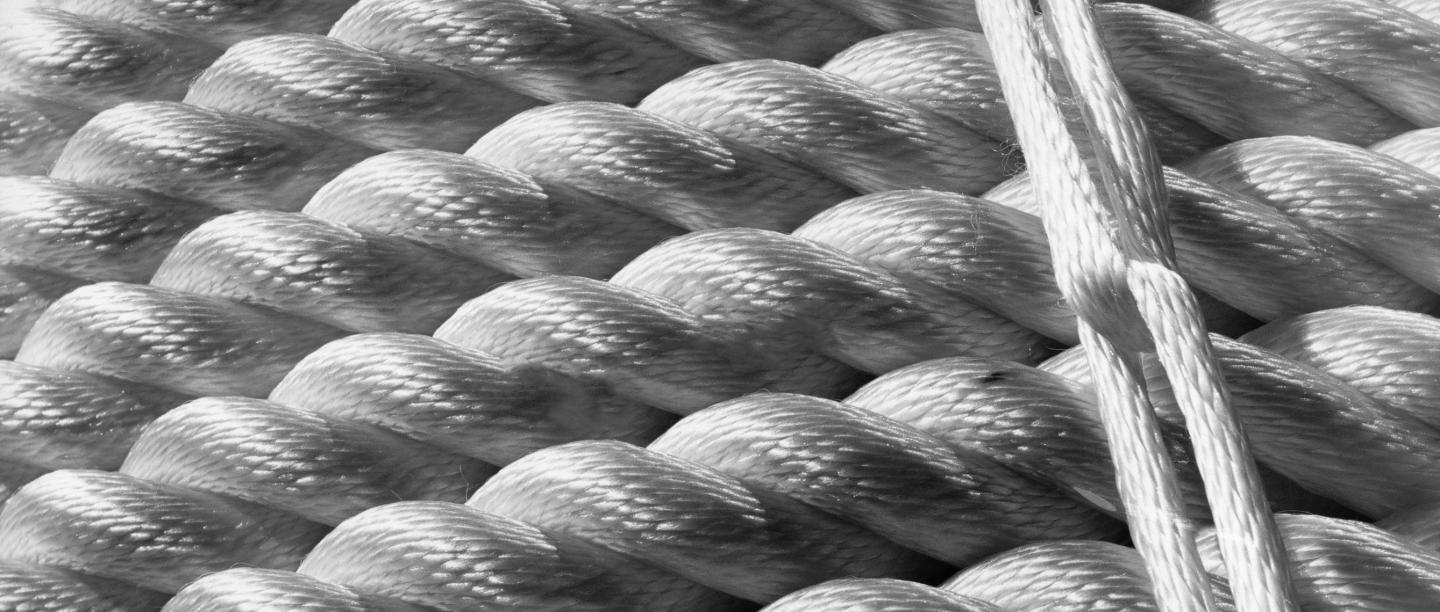

Heidersberger—who was born on June 10, 1906 in Ingolstadt and found his way to Wolfsburg after periods in Linz, Graz, Paris, The Hague, Copenhagen, Berlin, and Braunschweig—knew how to give free rein to his creativity in commissioned photography as well. With his flair for presenting architecture, creating arresting sightlines, and precise compositions, he quickly made a name for himself among architects of the Braunschweig School, but he also excelled at winning over a wide variety of advertising-photography clients.

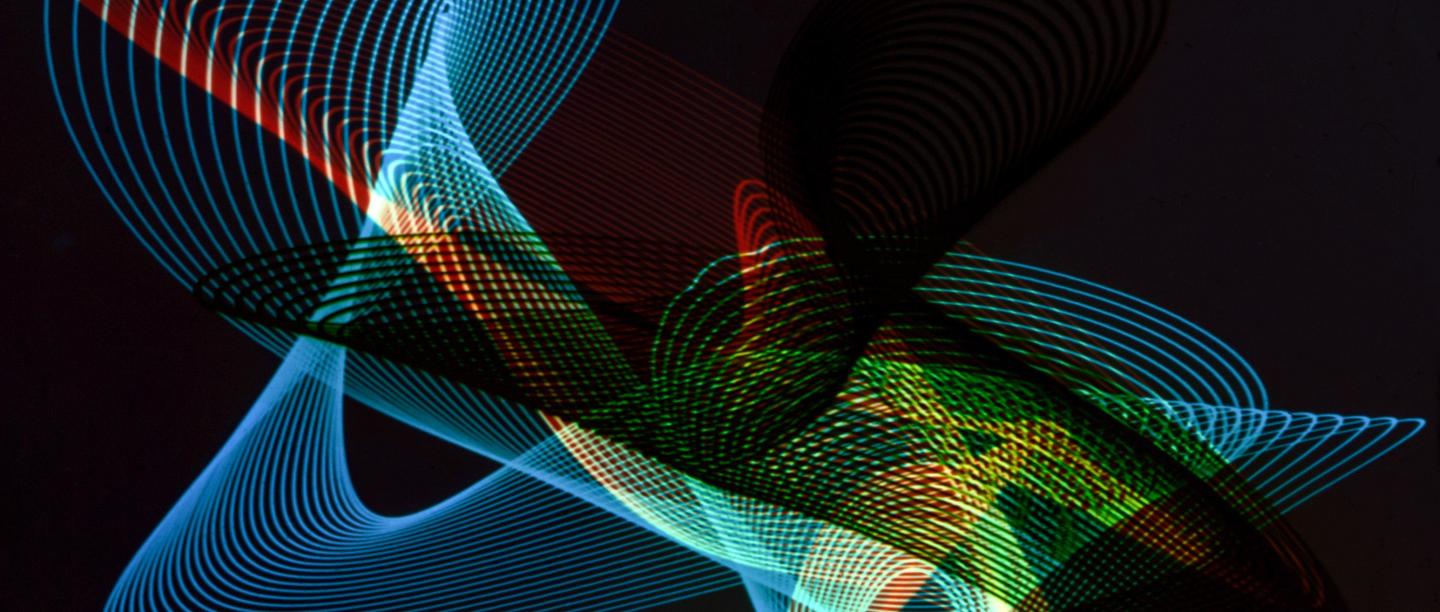

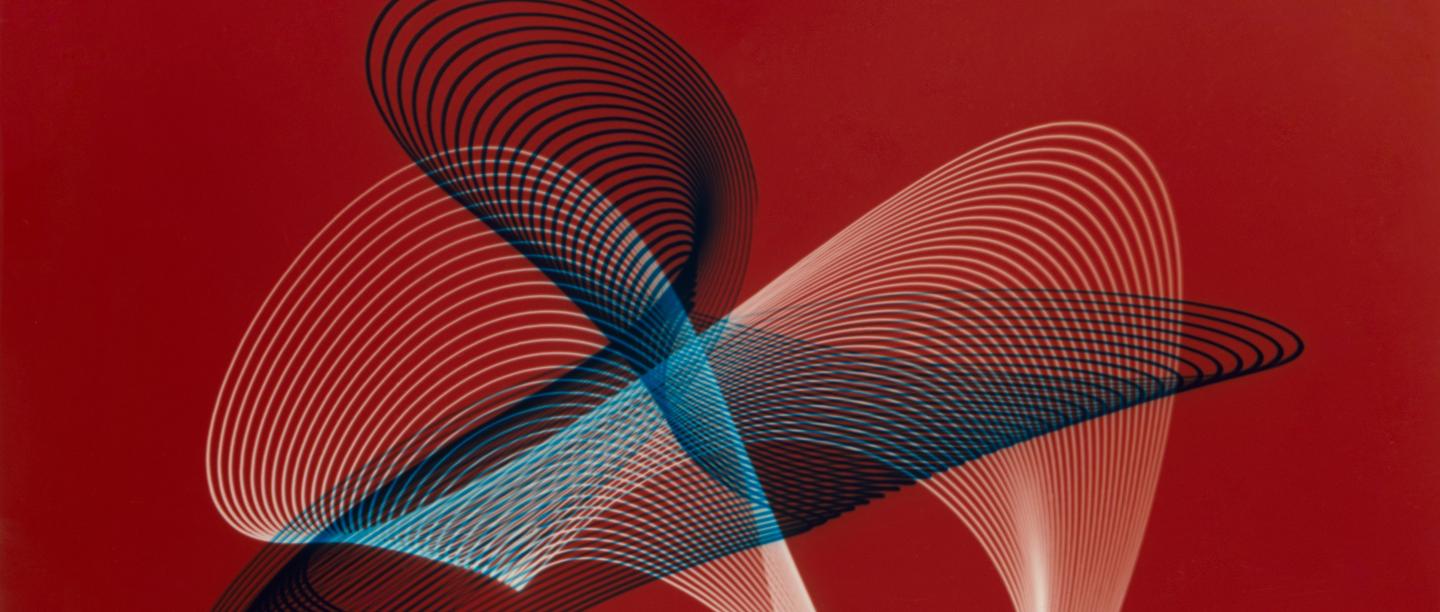

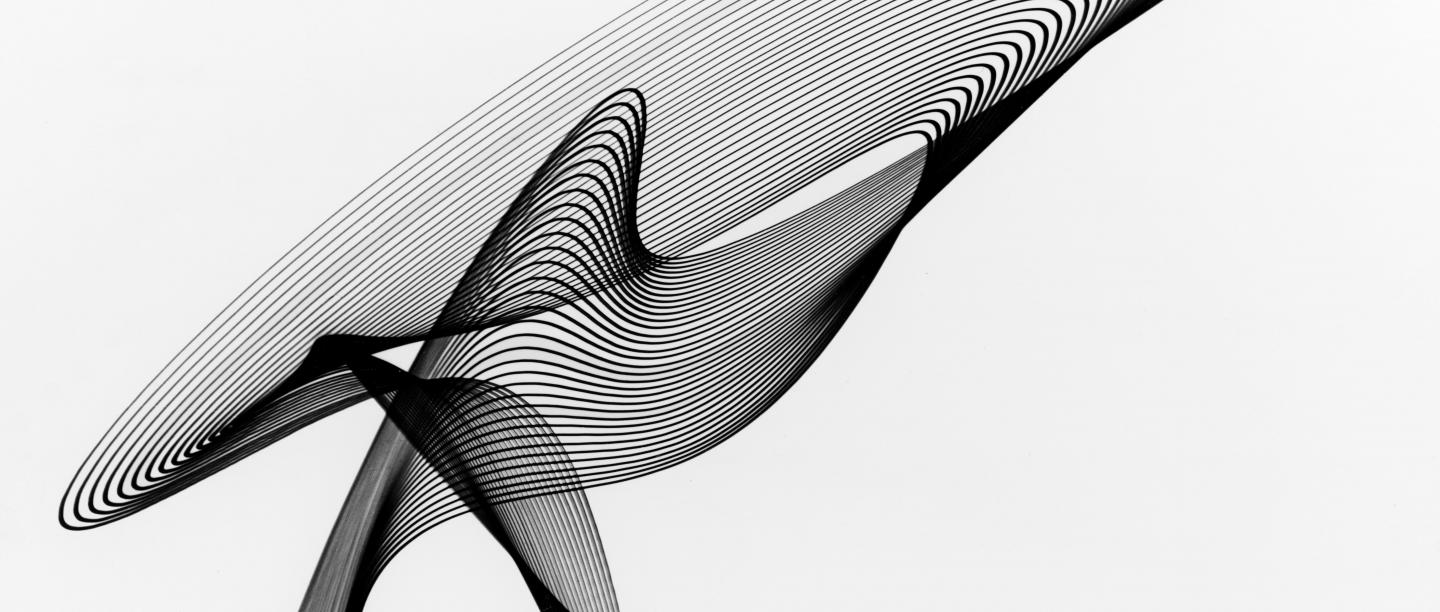

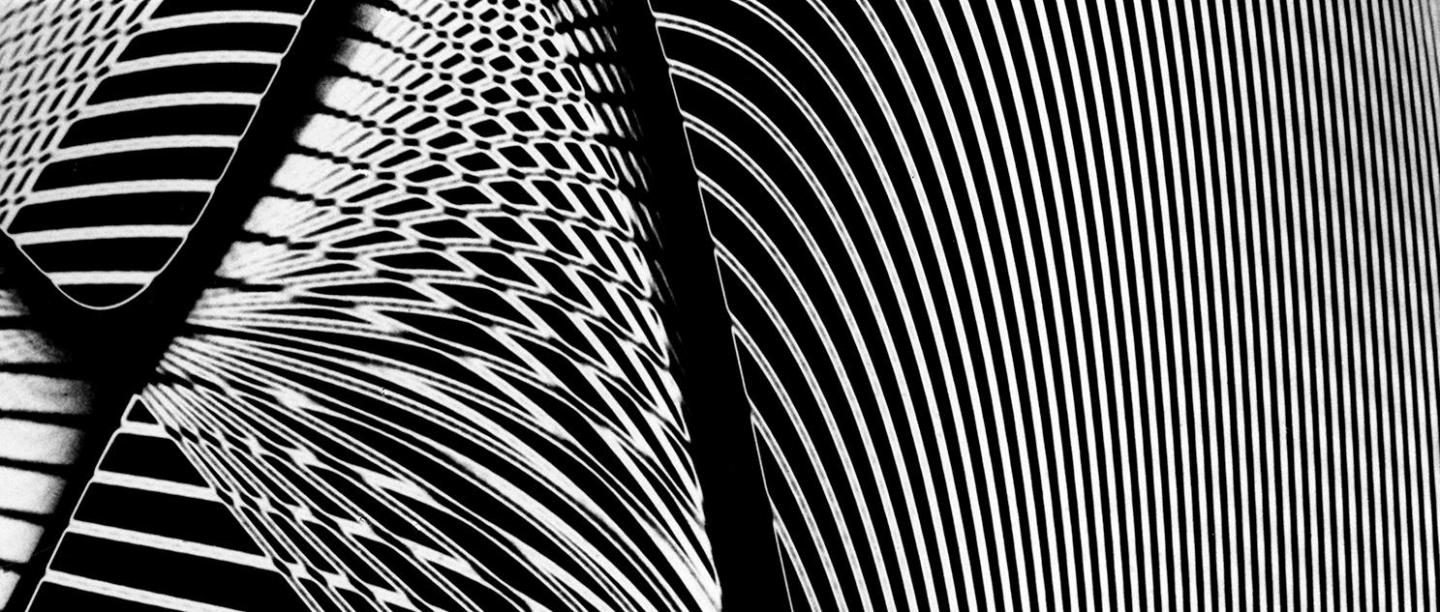

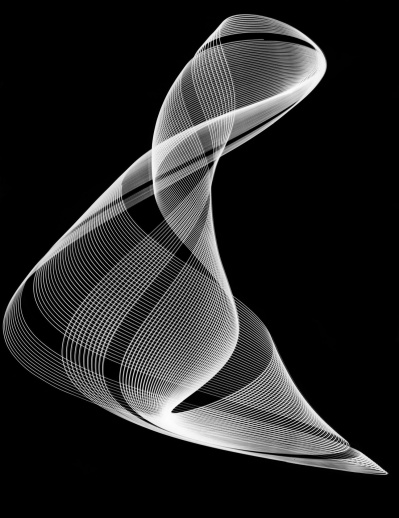

The contacts he made with the French Surrealists during his art studies in Paris, as well as his technical interests and know-how, also influenced his fine-art work. Among the best-known of these are his Rhythmograms, Lissajous figures he created with a specially constructed light pendulum machine, and his image series, Kleid aus Licht (Dress of Light), for which he used a light cannon to project circular and oval shapes onto the bare skin of a female nude. According to Rolf Sachsse, professor of design theory and history, Heidersberger’s work is characterized by an interest in the “entire production process” and not just in the final “result, which then might become a permanent museum object in its own right.” This is proof enough that the photographer is a “modernist, a true avant-gardist—and you can’t get any better than that in the twentieth century.”